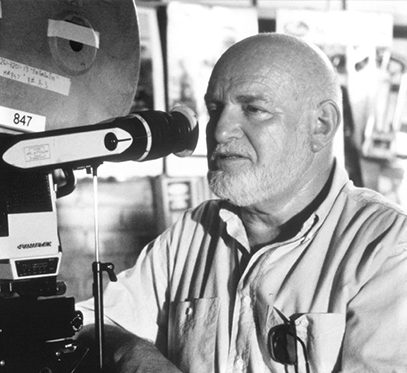

Photo of the Combe Gibbet in West Berkshire, dated 2007. Image Credit: Simon Green / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain, (left). Photo of British director, John Schlesinger. Image Credit: Sense of Cinema / Non-Commercial Use, (right).

I still recall the first time that I saw the Combe Gibbet. It was a bleak and rainy day in February. As I approached the scenic rolling hills, a murder of crows filled the sky. Once they cleared, there it was perched up high on the skyline. You'd be forgiven for thinking it resembles an oversized telephone pole. I certainly did. Yet, more intriguing than the monument itself is its colourful past.

The gibbet stands atop a long barrow (a hill or mound), which was used as a communal burial ground during the Neolithic era between 4,300 to 2000 BC. Crikey. The Combe Gibbet name is often used to refer to both the gibbet and barrow, but this is incorrect. This area also became the site of a gruesome double murder during the seventeenth century. More on this to come. The allure of this grisly landmark did not pass the attention of Oscar-winning British director, John Schlesinger (1926-2003).

Long before he championed the British New Wave and rose to prominence in Hollywood with notable classics such as Midnight Cowboy (1969), Sunday Bloody Sunday (1971) and Marathon Man (1976), Schlesinger resided in Inkpen, a small agricultural community in West Berkshire.

Promotional material for Midnight Cowboy (1969), Sunday Bloody Sunday (1971), and Marathon Man (1976). Image Credit: IMDb / Non-Commercial Use.

Schlesinger, born in London, lived with his family at Mount Pleasant House in Inkpen. He studied English at Balliol College, a constituent college of the University of Oxford, between 1947 and 1950. During this time, he befriended future collaborator, Alan Cooke (1926-1994). Cooke went on to become a respected television director in his own right.

One Easter holiday in 1948, Schlesinger invited Cooke and some other friends to visit him in Inkpen. They toured the valley together and naturally this meant a visit to the iconic Combe Gibbet. This monument is situated on the parish boundary between the villages of Combe and Inkpen, hence why is sometimes called the Inkpen Beacon. It was during this outing that they stumbled upon the idea for their first amateur film, a silent 16mm black and white feature called Black Legend (1948). Schlesinger had previously made a film, but this one would cement his passion for filmmaking and help launch his career as one of Britain's most versatile and distinguished filmmakers.

History

Black Legend is a dramatic retelling of the brutal double murder of Martha Broomham and her son Robert perpetrated by her husband George and his mistress Dorothy Newman on 23 February 1676. George was a common thatcher from Combe and Dorothy a widow from Inkpen. One unfortunate day, Martha and Robert discovered the pair together. George and Dorothy proceeded to murder them. There are many variations detailing how the murders transpired. The most plausible version that the film follows is that the murderers bludgeoned Martha and Robert to death 'with a staff'. The couple then disposed of their bodies nearby in Wigmoreash Pond, subsequently known as 'Murderer's Pool'. Black Legend's film noir inspirations come to light through its characterizations. George is presented as abrasive yet easily manipulated, whilst Dorothy is portrayed as a conniving and twisted femme fatale who personally carries out the murder of George's young son.

George and Dorothy were tried and convicted of murder in Winchester, as Combe was still part of the county of Hampshire until 1895. The court sentenced them to death by hanging. Their sentence was carried out on 7 March. Like most films based on real events, Schlesinger's adaptation takes liberties with certain details, chiefly concerning the site of their execution. This did not take place at the gibbet. Instead, they were hung at the Eastwick Estate near Combe. Afterwards, their bodies were moved to a barn near Inkpen Common in what is today the Crown and Garter Inn. The barn later became nicknamed the 'Gibbet Barn'. Here, the local blacksmith fitted their corpses with chains and displayed them in a gilded iron cage on the Combe Gibbet as a deterrent to other villagers. This misconception has led to the barrow becoming known as Gallows Down. Unlike gallows, a gibbet's express purpose is to display bodies, not to execute them. George and Dorothy were the only bodies ever displayed on the gibbet.

A map highlighting the important locations related to the murders of Martha and Robert Broomham. Image Credit: Google Maps / Non-Commercial Use.

Production

Neither Cooke nor Schlesinger, both still undergraduates, possessed any delusions about the strenuous undertaking that awaited them. Their ambitious idea materialized into a painstaking production, riddled with problems and near misses. Schlesinger funded the film with loans from local acquaintances and his army gratuity, having served in the Royal Engineers during the Second World War. Under the banner of Mount Pleasant Productions, the film entered production with a measly budget of £250, then a substantial sum. These financial constraints forced the reluctant filmmakers to shoot without sound. Filming took place over a fortnight during a cold and windy September, since the filmmakers soon had to return to university for the start of their autumn term. They planned for a New Year release. First-time directors, 400 different shots, multiple locations, dozens of inexperienced cast and crew and only two weeks to get it all done. What could possibly go wrong?

An original casting call for Black Legend (1948), dated September 1948. Image Credit: Newbury Weekly News / Non-Commercial Use.

The pair recruited their main cast from the Oxford University Amateur Dramatics Society. Otherwise, they depended on the goodwill of family members, friends and neighbours from the surrounding villages of Kintbury, Hungerford, Inkpen and Combe to fill the roles of the villagers. Schlesinger recalled how they had to ‘beg, borrow, and steal’ to produce this film. His cast and crew occupied the floors and tents in his house and garden. His parents provided the catering. The economic repercussions of the War which had only concluded three years earlier were still prevalent. Petrol rationing was enforced, which affected the transportation of crew and equipment between filming locations. Female extras found a suitable new use for their blackout curtains by turning these into dresses!

Ena Norton-Morgan, who played the leading role of George's wife, Martha, lent her real-life home of Rolf's Farm in Inkpen to the production, which doubled as her character's house. Schlesinger and Cooke both made brief appearances as the Judge and Prosecutor respectively during George and Dorothy's trial scene. It was in large part thanks to this extraordinary community effort and patience that the film was able to be made.

Playing the part of the village idiot 'Mad Thomas' who supposedly witnessed and reported the couple's crimes to the authorities is none other than esteemed British actor, Robert Hardy (1925-2017). Hardy attended Magdalen College, a constituent college of the University of Oxford. Like Schlesinger, he studied English and became involved with the Oxford University Amateur Dramatics Society. Hardy enjoyed a long and illustrious career both on stage and screen. He is most recognizable to younger audiences as Cornelius Fudge, the Minister for Magic in the Harry Potter franchise and J.K. Rowling's answer to British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain.

Clipping of the cast list from the original film programme for Black Legend, (left). A headshot of British actor, Robert Hardy. Image Credit: Filmweb / Non-Commercial Use, (right).

The filmmakers sourced props from Newbury Museum, now West Berkshire Museum. Specialist equipment was also constructed for the film, including a mock gibbet. This was deemed necessary since the gibbet that appears in the film was in a dilapidated state by this time. There have been no fewer than seven gibbets erected on this site.

The first was constructed in 1676, but eventually rotted away. The second assumed its place in 1816, but was struck by lightning at some point between 1835-1852. They built the third gibbet around this time, but this suffered irreparable damage due to gale-force winds in October 1949. The fourth gibbet was erected in May 1950, but was vandalized and cut down twice in May 1965 and October 1969. The fifth gibbet was erected in 1969/1970, but blew down in the winter of 1977/1978. The sixth gibbet was installed in 1979 but was also cut down in September 1991. Local authorities and villagers installed the seventh and final gibbet in 1992.

So, what we see today is very much the original gibbet in a Trigger's broom sort of way.

While the actual gibbet appears throughout, the filmmakers set up the mock example on a different hill elsewhere for the infamous hanging scene. The Inkpen-based sawmill, James Edwards & Sons, constructed the mock gibbet. The same company also built the fourth gibbet erected in 1950. One detail the filmmakers chose to imply rather than show explicitly was the hanging itself. Recalling my past experiences with student filmmaking, I would say this was a wise decision. But they tried! In the February 1950 issue of eminent film publication Sight and Sound, Alan Cooke recounted his experiences with the film:

'...one idea for an effect in the hanging scene wrecked the camera, which had to be rushed up to London with the loss of a day of sunshine'.

As far as I can tell, they still used this shot in the finished film!

The end result made quite an impact following its initial release. Screenings were held in Inkpen, Kintbury, Thatcham, Newbury, Oxford and London. The British Film Institute (BFI) invited the creators to show the film at a meeting of the Federation of Film Societies in London. Sir Michael Balcon, a seasoned English film producer, invited Schlesinger to screen the film at Ealing Studios. This did not end well according to Schlesinger! The main reason for this was because the film was recorded without sound, so they had to synchronize the music score and voiceover narration recorded by Cooke on a twin turntable live during each exhibition. No pressure! This complication resulted in screenings of varying degrees of quality.

Photo of a western electric twin turntable used in early silent cinema to synchronize music and sound effects to silent films, introduced in 1928. Image Credit: Powerhouse Collection / Non-Commercial Use.

Legacy

Over seventy years have passed since Black Legend first introduced itself to the world. Still, it remains a proud and treasured part of Inkpen, Combe and West Berkshire's cultural heritage. While a little rough around the edges, the film is quite impressive and does not suffer from its lack of sound as the filmmakers had initially feared. Schlesinger himself preferred Black Legend to his subsequent collaboration with Cooke, The Starfish (1950), a dark fantasy film shot with sound in Cornwall. I have to concur.

Today, screenings of the film are few and far between. The Watermill Theatre in Bagnor near Newbury hosted the last notable screening in 2011. The event was attended by surviving cast members including Robert Hardy himself. Hardy also assisted residents of Inkpen and the BFI with the restoration of Black Legend, as the original music and narration had long since been lost. In 2000, Hardy re-recorded the voiceover narration previously recorded by Cooke.

A collection of stills from Black Legend. Image Credits: Courtesy of BFI Southbank London.

Photo of the surviving original cast of Black Legend, including Robert Hardy (second from right), at a screening of the film at The Watermill Theatre in Newbury, dated March 2011. Image Credit: Hungerford Virtual Museum / Non-Commercial Use.

Black Legend has resonated within our collective memories for a number of reasons. First, it is exemplary of how short and low-budget feature films can be used as a viable commercial tool to attract industry professionals and investors, a source of immense pride for both Schlesinger and Cooke. Both men recognized the value of taking risks and learning from failure in independent filmmaking. As a young filmmaker myself, I find it inspiring how a local lad set out to realize his grand vision, even though this venture could have gone disastrously wrong at any point!

Black Legend also showcases the early trademarks that would define Schlesinger's filmography. Among these include his objective, voyeuristic style spurred by his genuine interest in people, something also evident in his later documentary work. Another staple of Schlesinger's work is his inclusion of character archetypes such as the flawed underdog, loser and non-conformist. Marathon Man sees a troubled yet mild-mannered graduate (Dustin Hoffman) challenged and forced to compromise on his principles once he is pitted against a rogue Nazi war criminal. Chloe Walker, a writer for the BFI, echoes these observations.

'A powerful ability to paint richly empathetic portraits of characters in unconventional relationships would become his trademark...

...Schlesinger is far more interested in exploring than judging; the messy necessity of compromise was always more dramatically fertile ground for him than clear-cut moral binaries'.

These points extend to include his fascination with unconventional relationships, something close to Schlesinger's heart as a homosexual. Such themes feature prominently in Midnight Cowboy, a bittersweet exploration of masculinity and homosexuality, and Sunday Bloody Sunday, a dramatic tale of a polygamous relationship between a gay Jewish doctor, a young male artist and a divorced middle-aged woman.

Schlesinger's affinity for visually striking and distinct settings also shines through his films. Whether this is the seedy underbelly of 1960s New York City in Midnight Cowboy, the gloomy industrial centre of northern England in A Kind of Loving (1962), or the serene backdrop of the Dorset countryside in Far from the Madding Crowd (1967). Evocative locations are the pulse of Schlesinger's films. His grounded realism presents a welcome antidote to Hollywood excess and splendour. All of this goes to illustrate why Schlesinger became such a major success and why we are still discussing his films today.

A digitized version of the silent film Black Legend is currently available to view in the BFI Reuben Library at BFI Southbank London.

Comments